That day in 1990, as she followed up on a classified ad in the ‘Whig Standard’—“Land for Sale”—[Rena] was pondering what it really means to be educated. In time she would come to believe that her basic education should include knowing how to build a little cabin on land you call your own. Picture her cabin. It sits on a rocky, treed outcrop overlooking a lake some twenty acres in size, a clear and ancient trout-filled lake ninety feet deep in the centre. The cabin is modest in size, with a ladder leading to a little loft at the south end. There is no electricity (though the plan is for solar power one day) and water comes from a small hand pump at the sink hooked up to a rain barrel outside.

Every item in the cabin—the tables and chairs and little wooden wall cabinets, the twin propane tanks outside for the small fridge tucked inside one of the mouseproof cupboards, the board-and-batten pine that sheaths the exterior, the two woodstoves, windows, doors—all this was either brought in along the mile-long trail or rafted over from [the other side of the lake]. And lest you think the raft option is a breeze, consider that both cabins sit on promontories. Ever tried to move a woodstove across a room, never mind up or down a rocky incline? I imagined ropes and boards and rollers, teams of sweating men using trees as leverage, progress measured in inches. Like ants moving the rubber tree in that old song or the pyramid builders of ancient Egypt, the movers would have needed equal parts optimism and savvy… I thought of Adam Smith’s old dictum, the one he wrote in Wealth of Nations in 1776: “The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it”. By that reckoning, Rena’s tiny cabin is a priceless castle.

She had help, of course. The crew would include her husband plus friends and high school students there to learn about building in the wilderness. But Rena, who had joined the building crew when the old schoolhouse in Yarker was gutted in 1984 and renovated to become their splendid house, had learned a thing or two about construction. About batter boards and building tubes, about plumb, level, and square. She designed her cabin, got the design approved, and either supervised a crew or worked alone as the cabin took shape in 1993. She still has the building inspector’s report (he paddled over in a canoe), his blessing proudly displayed in a scrapbook called “Beating Around the Bush.”

— Excerpts from ‘Harvest of a Quiet Eye: The Cabin as Sanctuary’, by Lawrence Scanlan (2004, Penguin).

PARTHENON (Sleeping Cabin) 2003

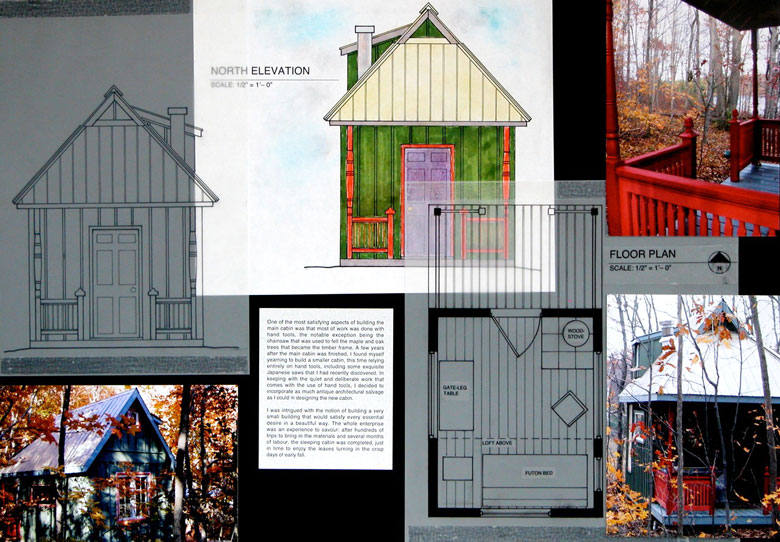

A few years after the main cabin was finished, I found myself yearning to build a smaller cabin. I was intrigued with the notion of building a very small dwelling that would satisfy every essential desire in a beautiful way. The footprint of the sleeping cabin is a mere 108 sq. ft., with an additional 54 sq. ft. porch.

In building the sleeping cabin, I relied entirely on hand tools including some exquisite Japanese saws. In keeping with the quiet and deliberate work that comes with the use of hand tools, I incorporated as much architectural salvage as I could in designing the new cabin, integrating old materials along with old technology. The whole enterprise was an experience to savour: after hundreds of trips to bring in the materials and several months of labour, the sleeping cabin was completed, just in time to enjoy the leaves turning in the crisp days of early fall of 2003.

One of the most satisfying aspects of building the main cabin was that most of work was done with hand tools, the notable exception being the chainsaw that was used to fell the maple and oak trees that became the timber frame. A few years after the main cabin was finished, I found myself yearning to build a smaller cabin, this time relying entirely on hand tools, including some exquisite Japanese saws that I had recently discovered. In keeping with the quiet and deliberate work that comes with the use of hand tools, I decided to incorporate as much antique architectural salvage as I could in designing the new cabin.

I was intrigued with the notion of building a very small building that would satisfy every essential desire in a beautiful way. The whole enterprise was an experience to savour: after hundreds of trips to bring in the materials and several months of labour, the sleeping cabin was completed, just in time to enjoy the leaves turning in the crisp days of early fall.